This week, I’m printing the interesting info I received from Vince Consolo, who reads my columns in several publications and is a true Packard owner and insightful “Packard pro.” The numerous communications we engaged in went on for several weeks, with Vince responding to my previous columns on the fall of Packard when it merged with already “cash strapped” Studebaker. Here’s Vince’s excellent explanation (with a few of my additions) of what happened to Packard utilizing Vince’s four “fateful “arrows” that brought the company down.

Q: Hi Greg and I still own my beloved 1955 Packard 400 2-Door Coupe, finished in Rose Quarts on the main body, and Polar white on the beltlines and roof. I purchased the car back in January of 1984, six months before I graduated from high school, 38 years ago. I’ve finally gotten all the mechanicals finished and the engine alone cost me $8,300 to have it rebuilt. Yikes! But it’s my baby and after all these years.

My work life has been in business organizational management the last few years. I got my B.A. in Liberal Studies from Antioch University and my master’s in organizational management from Antioch at the Los Angeles campus. I think I should be doing something more automotive related in an academic or creative way I think. (I should have been a writer like you, LOL.)

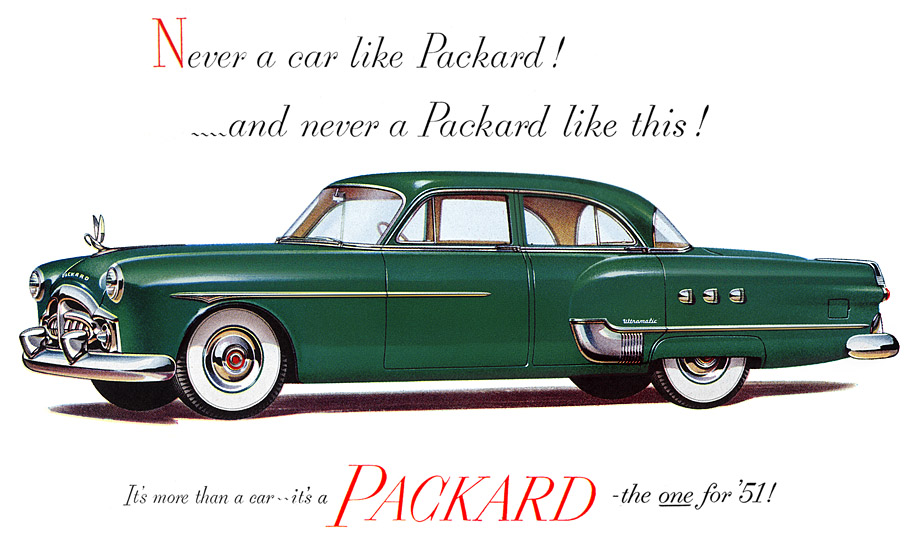

Reader Vince Consolo owns this 1955 Packard 400, one of the last real Packard’s produced. Consolo bought the car 38 years ago when he was graduating high school. (Consolo Collection)

You mentioned in our conversations you thought I should explain more about what really happened to luxury brand Packard, its future failure, and expanding on what you’ve touched on a bit in the past.

Let’s start with Hugh Ferry, Packard Finance executive and who had been there since the 1920’s and Warren Christopher, who was the President and General Manager of Packard from around 1934 or so until he was replaced by Ferry in 1951. Christopher was a former General Motors Production efficiency executive and learned car making the GM way and thought he could do the same thing with Packard.

Christopher took over from James Alvan Mc Cauley, who was the Chairman at the time. Mc Cauley led Packard longer than the original Packard brothers did when they started Packard back in 1899. By the mid 1930’s, the depression was still raging and small “independent” automakers were dropping out of business because they didn’t have the large cash reserves to ride out the “low sales” depression. Mc Cauley knew he had to do something as there were not enough buyers for its “Senior” (luxury) cars for the well to do, including clientele like royalty, celebrities, captains of industry and the like. In order to protect its cash reserves and bring sales up, Mc Cauley hired Christopher to turn things around for the company.

I have read that Mc Cauley felt he wasn’t the man to solve this dilemma. Although Mc Cauley was adept at running Packard during good times when money was affluent, he was not a mass production man like Christopher. McCauley was more of what I’d call a “gentlemen’s” executive who came from a different era of business dealings and corporate management. Christopher pitched the idea of a “Junior” Packard car priced somewhere in the Oldsmobile or Pontiac range to accompany the “Senior” luxurious cars. His idea was to raise sales to a point where Packard wouldn’t have to dig into its cash reserves and thus survive the depression. The board of directors and Mc Cauley liked the idea and gave Christopher the green light.

And it sure was a success.

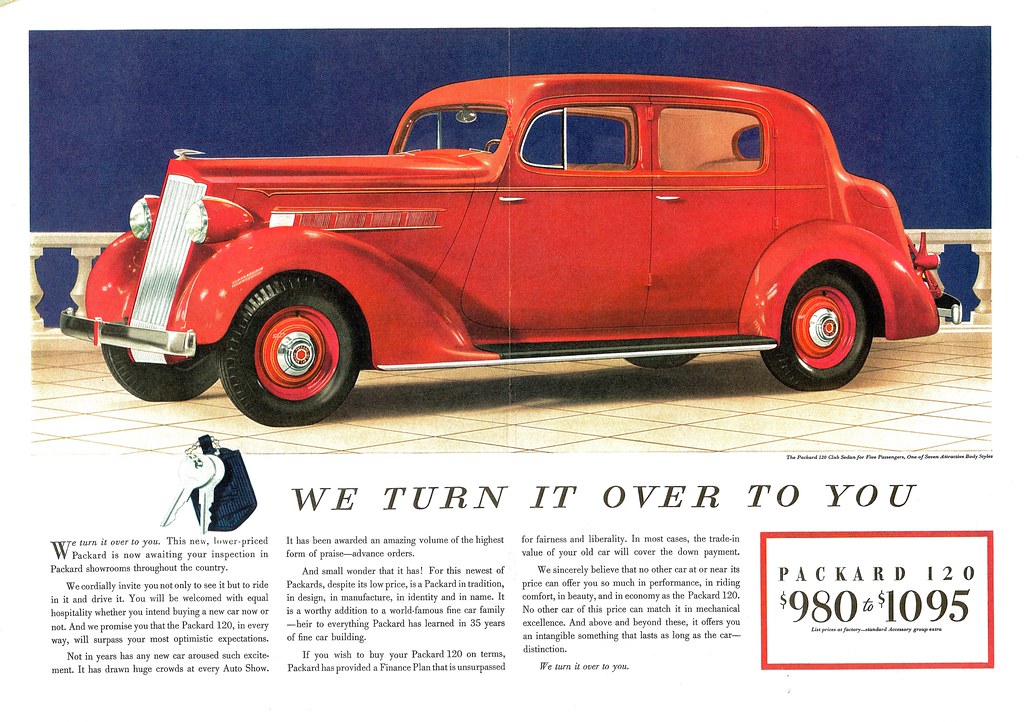

Packard’s first low priced “Junior” car was the 1935 Packard 120. It was also the first Packard that cost less than $1,000. (Former Packard)

The “Junior” car was the 1935 Packard 120 and was Packard’s lowest priced eight-cylinder car (less than $1,000). It was a huge hit and helped save Packard. Christopher, meanwhile, was not a huge fan of the “Senior,” and many times called them “that gosh darn ‘Senior’ crap!” This was one trait that Mc Cauley and the board didn’t see coming or reign in, Christopher knowing that such a move might carry Packard downward in prestige and reputation as an exclusive car. That wouldn’t be clear until after the war when all the damage that had been done to Packard’s credibility and prestige as an exclusive luxury automaker took place.

Fast forward to after the war.

The depression and the war were over, and people were flush with cash. They were weary of austerity and war and desperately wanted to return to more prosperous and happier days. During the war, the Packard employees emptied out all machinery dealing with cars to concentrate on building wartime products at its plant. Packard made repairs and upgrades to the facilities, rebuilt the proving ground test track, moved all the machinery to make cars back inside from being stored outside under tarps coated in Cosmo line, a rust proof coating. This was expensive because some of the machines suffered damage from sitting outside for nearly four years.

Arrow number One: Now here is where the first fatal arrow was fired. Christopher insisted on following his past ways of running Packard. Mc Cauley and the board didn’t reign in Christopher and tell him they were going back to making expensive luxury cars. Had Packard taken the right road and elected to reverse course by selling nothing but senior prestige cars; the irony here is that they would have sold every car they could have shoved out the door at the factory. Packard would have made a boatload of money on top of fortunes made from war contracts and monies already in the bank before the war. This would have seen Packard through for years and most likely not having to merge with a weak independent automaker and yet also remain totally independent.

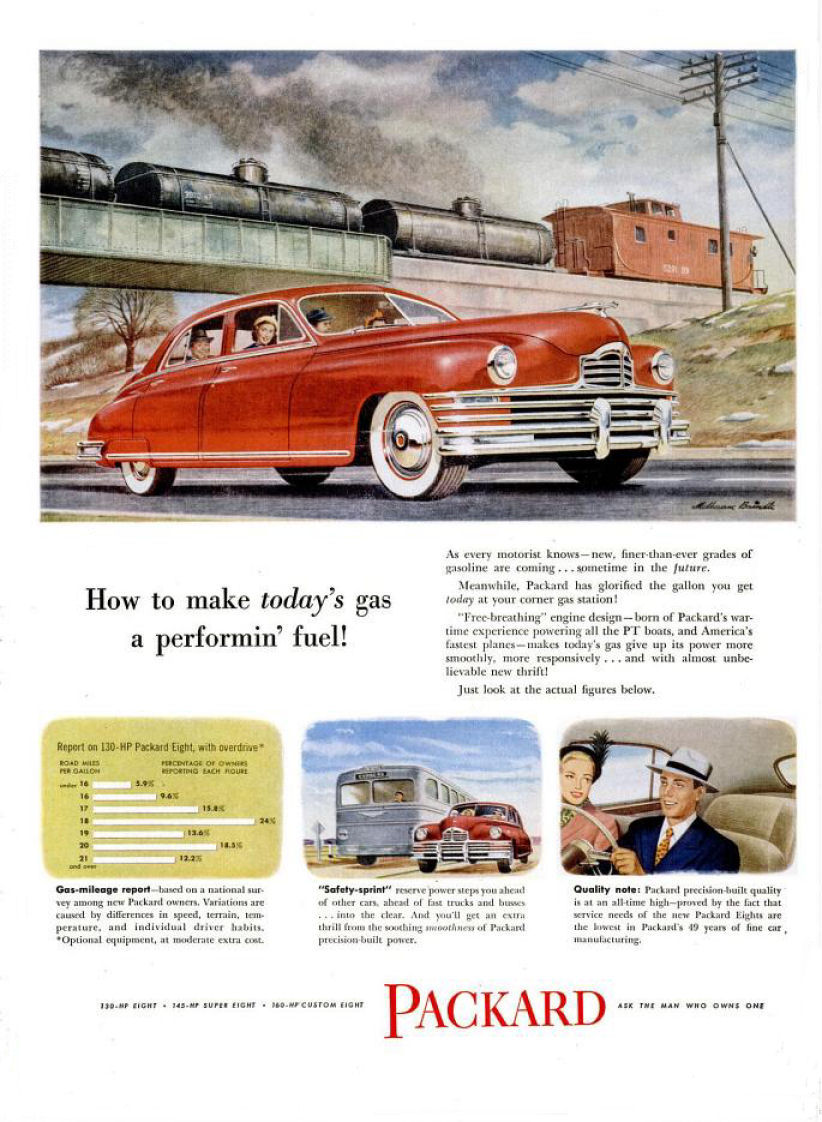

The 1940s featured the “bathtub” era of car design, and Packard utilized the design too long for both management and the public. (Former Packard)

Arrow number Two: besides the latter, Christopher warmed over the post war designs with different doors that would not work another year on the “bathtub” style cars (late mid to late 1940s). They had enough working on these cars that the public didn’t warm up to very much, and many in these departments threatened to quit if a new body style was not produced for the 1951 model year. Management decided on a new body after much pressure had been exerted by both the inside people and the public.

Christopher refused to make a new body until the tooling costs of the warmed-over prewar designs were paid for. That might have taken another year or two to do. Christopher got into many arguments with the board over these issues, resulting in his contract being terminated effective Jan. 1, 1950. He left in December of 1949. Aforementioned Ferry took over in 1951, and then James Nance became President and General Manager of Packard in May of 1952.

Arrow number Three: William “Bunkie” Knudson was a senior executive at GM who earned the military rank of General in the Army and worked in procurement for the government. After the war, Knudson went back to private industry until Dwight Eisenhower won the 1952 election and Knudson was chosen as Eisenhower’s Secretary of Defense. As the story goes, Knudson gave many of his old buddies at GM lucrative defense contracts and took existing ones away from other defense contractors, including Packard.

Packard could ill afford the loss of those contracts while sales of the cars were slow during the 1953 and 1954 sales war started by Ford and Chevrolet. This cut into Packard’s sales and that of the other Independents as well when they could least afford it. Knudson and GM always denied this, but it was true. (Knudson played a major role in GM racing success, too, and worked closely with Smokey Yunick and his Pontiac and Chevrolet winning NASCAR racecars. If Smokey needed something, Knudson made it happen.)

Arrow number Four: The merger with Studebaker was right around the corner and Nance and his board were leery of this prospect of getting tangled up with Studebaker. Studebaker had a much higher break even and profit-making milestone than anyone knew of. Nance sent his finance man, Walter Grant, to South Bend, Indiana to do a complete examination of Studebaker’s financials. Beverly Rae Kimes in her book, The Packard Story, said that Grant came back to Detroit and went to see his boss at Packard’s executive office, informing him that Studebaker’s breakeven point was much higher than anyone was aware of. It had been reported that their breakeven was approximately 165,000 cars. In reality, it was much higher and more like double at around 325,000 cars. (You can check my numbers and memory if you need to, but I’m in the neighborhood.)

Nance, Grant, and the board knew Studebaker could never achieve those numbers without coming out with all new body styles and models.

Still, the Packard-Studebaker merger went through officially on Oct. 1, 1954, when Packard bought Studebaker, which had more dealers nationwide.

By the 1st of January of 1955, Packard finally introduced its ‘55 models many months late. A new factory and upgrade (formerly a Chrysler plant) cost $55-million dollars on a Packard “modernization program” and took several months before the quality came up and the bugs were worked out of the new cars. The new engine and transmission plant in Utica, Michigan was much smaller than the old Packard plant on East Grand Boulevard.

Turns out it would have been much cheaper to renovate the old plant than the new one-story layout as advised by one Ray Powers, a friend of Nance’s that came from Ford. Powers was Nance’s Production and Facilities manager and Kimes noted in her book it was “irretrievably bad advice from Powers.”

The trend back in the 1950’s was to move into one story plants instead of the still common multi-story plants that had been the norm since the beginning of the auto industry in the U.S. Ironically, GM, Ford, Chrysler, Kaiser Jeep, Studebaker, and even Nash and Hudson (later AMC) had multi-story plants in addition to single story plants, simultaneously. So the idea that Nance could not renovate the original plant was a bad decision indeed.

By mid-1956, Nance and Packard were on the ropes and approaching bankruptcy. The money borrowed from the banks based on the merger working was running out fast and the banks made clear that if Nance ran below a certain amount of credit left, things would be bad. At one point the board considered total liquidation, which maybe would have been better for poor old Packard rather than suffer the humiliation of just being a third-class vehicle and being called a “has-been.”

Nance and Chairman Hugh Ferry named a Mr. Hurley, then CEO of Curtis-Wright aircraft, to a management position in the company in exchange for defense contracts and some cash infusions to stave off complete liquidation, which President Eisenhower did not want on his watch. The failure would have been the largest corporate collapse in U.S. history up to that point.

Still, Nance ordered the Packard line shut down in July of 1956. It was one his last acts or orders as President of Packard. He left a couple of weeks later and Harold Churchill, Nance’s General Manager of the Studebaker Division, took over as President and General Manager of the company.

Interestingly, the Packard part of the Studebaker-Packard’s corporate name was deleted in 1962 because it was felt the Packard name was no longer relevant to the company.

Also, a woman from my old church in Los Angeles went to school with Harold Churchill’s daughter back in the 1960’s. She went to his home many times and said they were nice people and their home was a mansion.

Greg, this is my synopsis and by no means is the only factor that affected Packard’s demise. There were many other factors that played a role here, but these “arrows” are the worst ones in my opinion. Packard management was still stuck in the “Gentlemen’s Handshakes of Business Dealings,” and slow at adapting and changing to the modern ways of business. It hurt them dearly.

Signed, Vince Consolo, Yakima, Washington.

A: Thanks so much Vince. You’ve unraveled, for all my readers, pieces of the puzzle not usually written about in how the great luxury Packard nameplate came to a sad ending. Your memory, writing ability, and excellent research made this an enjoyable feature.

(Greg Zyla is a syndicated auto columnist who welcomes reader questions and comments on collector cars, auto nostalgia and motorsports at greg@gregzyla.com).

Be the first to comment on "Cars We Remember / Collector Car Corner; The four ‘fateful’ arrows’ that killed the famous Packard motorcars"